The Traveller universe is a dangerous place. Pirates haunt trade routes; skirmishes and wars leave shattered hulls and bodies; and even in the absence of a living enemy, space itself is an unforgiving foe. What happens to the remnants of these losses? Enter the salvager.

What is salvaging?

Salvaging is a potentially lucrative profession relying heavily on luck, planning, and excellent sensors. Being hired by patrons to salvage a lost ship is a classic hook for a Traveller adventure. However, even in the absence of connections, salvaging can be done. Not that it will be easy.

Legality

This is the trickiest bit. Historically (and currently) on earth, an arrangement must be made with the owner of a ship in order to salvage it, typically under a “no cure, no pay” clause. The salvager contracts to recover the ship and return it to the owner, in exchange for money. Even when things may seem clear cut, these contracts may get caught up in court for years before the salvager gets their money.

Things can be looser in your Traveller universe, however. In my current setting, for instance, there are several areas where wars were fought during the past couple of years. The victors were pretty good about salvaging their own losses, but enemy losses can be found. Legally, those are considered free to the finder, though the salvager is required to bring along a sealed, untamperable recorder with which to determine the identity of the ship.

Finding your wreck

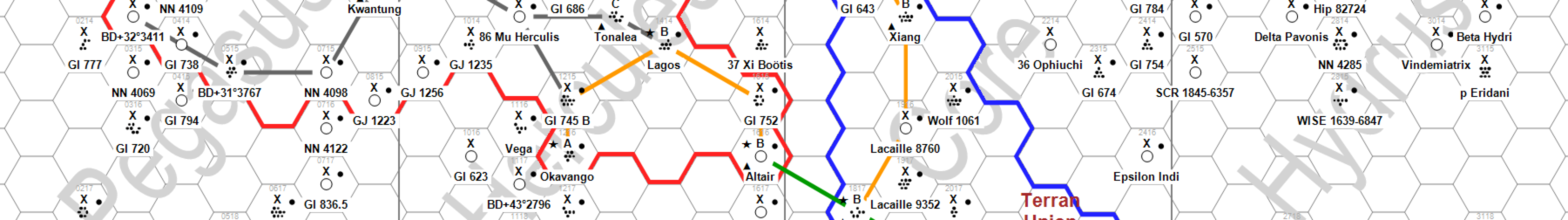

It’s important to understand that space isn’t simply swarming with wrecks waiting to be salvaged. Wrecks will cluster around trouble spots: War zones (or areas where wars were recently fought); areas of heavy piracy; areas with dangerous environments. A prospective salvager needs to keep their finger on the pulse of the subsector, so that they understand where the likely wrecks are. This, of course, is a fantastic hook for adventure: If wrecks destroyed by pirates are in an area, then there should be an increased danger of piracy in that area. If heavy radiation around a gas giant sometimes wreck ships that are trying to refuel, then that danger lies in wait for the salvager, as well.

Once a likely spot is identified, then the salvager needs to start looking. Wrecks are effectively running silently, so ships are at a disadvantage when scanning for them. Standard civilian shipping normally has a 0.5 light second sensor range. When trying to find salvage, they will be unable to detect a wreck out past 0.25 light seconds. This is an area where a scout ship operating on detached duty has an advantage – their superior sensors can still detect a wreck out to 1 light second.

In my settings, a ship with civilian sensors that is actively looking for a wreck in an appropriate area has about a 2% chance per week of finding one. A ship with scout or military sensors has about a 4% chance per week of finding one. In 2d6 terms, a civilian ship needs to roll a perfect 2, while a ship with scout/military sensors needs to roll a 2 or 3.

Both the 1981 and 1977 ship encounter tables in book 2 result in ship encounters on high rolls. They are both somewhat vague about how often the roll should happen, simply stating that it should happen when a ship enters a system. Since most starships will go straight to the starport, or another planet, I rule that a ship that remains in space will make a roll once a week. Since finding a wreck happens with a low roll and a ship encounter happens with a high roll, the same roll can be used for both. Third party tables, likewise, tend to follow the same pattern. For instance, I personally am a huge fan of the encounter tables in Zozer’s SOLO – the tables go a long way towards establishing motives for encountered ships, and they provide a wide spread of ships in various situations. The tables in SOLO all generate encounters with high rolls, so I’m still able to use the same roll for finding salvage as well. Once salvage is found, simply determine the ship type randomly – I use the same ship encounter table, and just roll again until I come up with a ship type.

Condition of the wreck

A wreck is a wreck because it’s not a functional spacecraft. However, that doesn’t mean that everything on the ship is ruined. Once I know what sort of ship the wreck is, I’ll roll for each major component on the ship – jump drive, power plant, computer, turrets, weapons, small craft/vehicles, etc – using the following table:

| |

| Destroyed (Any weapons carried in a destroyed turret are considered destroyed) |

| |

| |

| |

| |

In addition to the condition of the components, I also roll for the condition of the hull. Roll 1d6. 1 = swiss cheese, 6 = wholly intact. This really only comes into play if the players wish to repair the ship and fly it.

Salvaging the wreck

Once I’ve identified a wreck and determined the conditions of its’ components, my players can begin salvaging. Computers, turrets, and the like can all be salvaged in one week, while larger components (drives, etc) require at least a week each. Roll 8+ on 2d6, applying the most skilled salvagers’ engineering skill as a positive DM. If the salvager is alone, apply a -2. Failure allows the salvager to try again in another week, but a natural 2 results in the component being destroyed. Note, too, in the table that if a turret is destroyed, then any weapons carried in the turret are also destroyed.

Normal salvaging of small components (computers, turrets, etc) can be done with the standard toolkits normally carried on a starship. In Book 3 terms, this is the electronic, mechanical, and metalworking toolkits. Salvaging large components (drives) requires a laser cutter to cut into the hull, as well as thruster packs to maneuver the component out of the ship. Once the component has been removed, it can be loaded into the salvager’s cargo bay.

Gear

Laser Cutter: (TL 10) Cr 10,000. A heavy duty laser designed to be powered by a starship power plant. Cased cutter weighs 50 kg.

Thruster Pack: (TL 9) Cr 100,000. A set of thrusters designed to move a 1-10 dton object over short distances in space. The thruster pack cannot move anything quickly. Massier objects may be moved using multiple thruster packs. Powered by integral power packs, recharged from a ship’s powerplant. Cased thruster set weighs 200 kg.

Pay me my money!

Legal salvage can be sold to a shipyard, scrappers, or other resellers of used components. The sale price for components is based on their condition, and the new price of the component. Disabled but repaired parts may be repaired to increase their value, while (at the referees discretion) components may be scrapped for spares to repair similar components. For instance, a beam laser that is salvageable for spares may be used in an attempt to repair a beam laser that is disabled but repairable.

Having a disabled component repaired costs 10% of the new price of the component. This makes it economically unviable to have a component repaired to sell – you will spend 10% of the price of the component in order to make 5% of the price of it. However, a skilled engineer can attempt to repair a component at a cost of 2.5% of the price of the component. Roll 8+ with appropriate DMs, the attempt takes a week. If another similar part is salvageable for spares, roll 8+ to find the parts needed. Failures can be re-attempted at an additional cost in parts.

Selling the location of the wreck

If other salvagers are working an area, they may pay a finder’s fee for the location of a wreck. Depending on the condition of the wreck, its location, and the nature of the other salvagers, expect to be offered between 1 and 5% of the new value of the ship as a finder’s fee. A hull with at least one salvageable drive (not necessarily repairable, just salvageable) should always be worth at least 1% of the new value of the ship. A hull with at least one repairable or operational drive is worth more.